A while ago I received an email from an old school friend, now living in the UK, who was at Cambridge University as an undergraduate at the same time as I was, from 1954 to 1956. He was catching up with whoever is still alive, and passed on some gossip to me about people I used to know. Amid the email chatter he wrote: “I see you got a mention in Sylvia Plath’s Journal”. This was news to me, but I finally caught up with the “mention” a few weeks ago, prompted by the arrival in Sydney of the movie “Sylvia”. I went to it out of curiosity to see how they had recreated the Cambridge of the 50s and whether the result tallied with own recollections. Gwyneth Paltrow seemed very much like the Sylvia Plath I remembered. I did find a number of minor inaccuracies, including my being cut out of a party scene, where, according to the Plath Journal, I was playing a guitar, but the main shortcoming, I thought, was in the casting of Daniel Craig as Ted Hughes. This was not the man I remembered, and not the man to whom Sylvia Plath felt so immediately attracted.

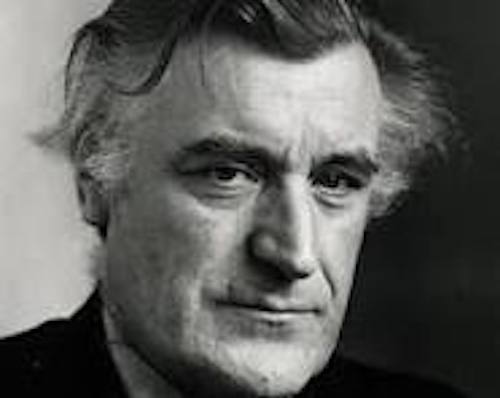

The misrepresentation of Hughes is not through any fault in Craig’s acting, nor even his slighter build. It is due to his lack of Hughes’ unique presence, which was partly due to his stature – he was a bear of a man – and partly due to his voice, which was effortlessly loud, like an actor’s, and partly due to his manner, which was dominant. He had a strong aura, and his aura was self-assertive, that of a natural leader. There was nothing effete about him. He was not an aesthete. He was a poet in the Elizabethan mode, hard drinking, hard talking, happy in a tavern .His physical presence made him attractive to women. The intellect and poetry were add-ons, though as his reputation grew, those attributes were, of course, part of his appeal. The combination was irresistible. At the time, I thought that some aspects of Ted’s machismo were assumed, a bravado facade, because it was easy for him. But subsequent events suggest that it was no act. It was the way he was. The essence of his being. He talked a lot because he liked talking. He was at ease with language. He was blunt and direct, and he didn’t suffer fools gladly.

Ted Hughes did me a great favour at Cambridge, during an encounter in a tavern, when I was the subject of a tirade from him, which I deserved, and which I’ll recount below. At the time, I felt very uncomfortable about his attack on me, but it did help me rediscover myself, after a period of great confusion, resulting from events in my final year at a Protestant boarding school in Belfast, Northern Ireland. Not a sympathetic place in which to live and be educated, in my opinion.

I met both Ted and Sylvia before they met each other. I do have some vivid recollections of each separately, but I none of their relationship or their life together – just some gossip passed from friends who did. The extract from Sylvia Plath’s Journal which involves me was written several days after the events it describes. To put her words in perspective, it helps to know that the gender balance at Cambridge University at that time, and probably still today, was very skewed by there being around 20 male colleges to only two female colleges. The female population of Cambridge was slightly augmented by the presence of foreign women studying English at an educational establishment which was entirely separate from the University – and an establishment in which male undergraduates took a great interest.

My situation was different to that of most undergraduates. As I was a resident of Northern Ireland I was exempt from the 2 years compulsory National Service in the military which all the other students had done. That made them all older and more experienced than me. Much more experienced. I was certainly very tentative with women, and for the first 18 months of my 3 years at Cambridge I did very little socializing; in fact I lived a positively monastic existence! But most other undergraduates, suddenly liberated from the army, were not restrained by inhibitions. There’s an entry for February 26 1956, during the period when she was attending Newnham College at Cambridge University, reading English on a Fulbright Scholarship. In fact, she was also studying French. So was I, and I think I must have first met her at a French lecture, possibly on the French 17th century playwright Racine, since she makes references in the Journal to “finishing the Racine”.

At any rate, the initial approach came from me. I chatted her up and, as it says in the Journal annotations, “dated her”. After describing depression, ‘flu and a withdrawal from the world, Sylvia Plath’s Journal continues, and I quote:

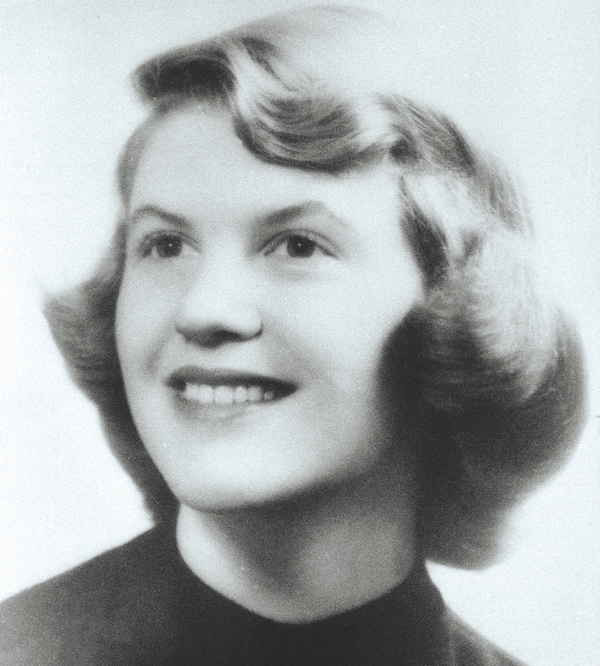

“Now, despite the twitch of a drying cold, I am cleansed, and once again, stoic, humorous. Made a few criticisms of action and had a chance to prove points this week. Ran through lists of men I knew here, and was appalled: granted, the ones I’d told to take off were not worth seeing (well, it’s true), but how few I knew were! And how few I knew. So, again, I decided, again, it is time to accept the party, the tea. And Derek asked me to a wine-party Wednesday. I froze, like usual, but said probably and went. It was, after the first scare (I always feel I turn into a gargoyle when too long alone, and that people will point.) it was good. There was a fire, five guitar players, nice guys, pretty girls, one Norwegian blonde named Gretta, who sang “On Top Of Old Smokey” in Norwegian, and a divine hot wine and gin punch with lemon and nutmeg which was good to savor and relieved the tremors I’d been having prior to the breaking of the cold. Then, too, a boy named Hamish … asked me out next week …”

It’s pleasing to know, even belatedly, that I was not on Sylvia’s ‘no’ list. At the time I didn’t even know there was one! I suspect I was an acceptable companion because I was neither pushy nor brash nor over-confident. But there is a good reason why I never took her out again. Four days later the aforementioned Hamish took her to a party where she met Ted Hughes. Apparently I was present. Her journal says “Derek was there, with guitar” - but I’m afraid, this far on, it’s hard to remember one party from another – too much punch? Sylvia also mentions “the syncopated strut of a piano upstairs”.

The fact that I don’t remember that particular party is, I think, significant, and this brings me back to the movie, since that party is re-enacted in it – and, regrettably, the producers have not depicted me there strumming my guitar. For the film they bring in a complete Dixieland band blasting out on a rostrum, and they fill the room with energetically jiving couples. A minor inaccuracy, for which I forgive them, But I can’t forgive them for the way they stage the first kiss between Ted and Sylvia. In her journal Sylvia describes this with the memorable phrase: “bang smash on the mouth kiss” and she also describes biting Ted on the cheek and drawing blood. The film has this encounter happening on the dancing floor in full view of everyone. If it had happened like that I would probably have seen it. But Sylvia Plath’s Journal makes it clear that Ted spirited her into another room, ostensibly to find brandy, then (quote) “slammed the door”. And then (quote) “when we came out of the room blood was running down his face.” A significant difference, in my opinion. Ted wanted privacy. Sylvia branded him to make their meeting public. She was the hunter. He was the hunted. A very important distinction, and one that is worth noting, in trying to understand what happened between them subsequently.

Her Journal continues the saga quite explicitly, and describes a change in roles. In April, Ted Hughes, on the prowl, begins to pursue her. He’s with a friend throwing mud at a window at 2.00am, thinking it’s hers. The film shows stones being thrown to an upper room in the drab red brick building where Newnham College housed students. The stone-throwing is accurate, but, unless she’d moved from her digs the film has it wrong. She wasn’t actually living in the college. When I cycled to Sylvia’s digs, tentatively calling by, it was a pretty cottage, in what I remember to be something like a field. I distinctly remember flowers, a little garden, a trellis. My most vivid recollection of Sylvia Plath is at the front door. Sylvia opening it. Talking at the door. Why is it this that I remember most of all? I think it’s because, even at the late age of twenty-one, it was still a great novelty for me being able to call on a woman I found attractive, and have her greet me at the door and let me come in.

I know that sounds extraordinary, but you need to remember that before coming to Cambridge at the age of 18, I’d been incarcerated in a boys’ boarding school for 10 years, and the only women I met outside school, during two months of holidays each year, were my mother, my sister and several very eccentric aunts. I lead a very sheltered existence before I arrived at Cambridge University. In fact, Sylvia Plath was one of the very few women, until that time, who took any notice of me. I remember finding her exotic, not only because she was beautiful, and blonde, but also because she was a real live American; and she was very smart. It probably set a standard for me. How many times did I call by? I can’t remember. But I remember her opening that door. I was shown in. We sat and talked. Where? I think it was in the kitchen? Talking about what? Poetry? Almost certainly. I’d had one small poem published in the University magazine Granta. But I had no ambition to become a published poet. I’d put aside wanting to be a composer. At this stage I’d become interested in acting. So although I was not on the ‘no’ list, clearly I was unable to meet her concerns. And I was not Ted Hughes, either. And she met him four days after I earned my mention in her diary.

I think I met Ted Hughes about about a year before I met Sylvia Plath. Thanks to one particular encounter I took another look at myself. I think if I describe this event, it’ll give you some insight into the impact of the Hughes personality. In order to explain what the nature of this encounter was, I’ll have to give an outline of my own background.

I come from a religious background, on both sides of my family. My paternal grandfather had been a Moderator of the Presbyterian Church in Northern Ireland; and my maternal grandfather, after abandoning a successful career as an architect in Belfast, had joined the British Bible Society to become an evangelical missionary in Africa.

Northern Ireland is a troubled country in which ancient conflicts involving religion, which should have been resolved centuries ago, are still rampant. Many people have left the country to escape this social contagion, and my own father, I think, made his escape to the colonies. Soon after graduating as a doctor he took a job in colonial Malaya, engaged in social medicine and malarial research. As a result, I was born in Penang. When the Japanese invaded Malaya, my mother, my sister and I evacuated to Perth. That’s Perth in Western Australia, not Perth in Scotland! My father was a prisoner of war at Changi in Singapore. The three years I spent in Perth were the best part of my childhood. After the defeat of Germany in WW2, and before the defeat of Japan, we returned to Northern Ireland.

Well, it was a return for my mother, but not for me. I never really adjusted to life in the UK. It was never home for me. My sister and I were thought strange for running barefoot on the beach in Belfast Lough. And my experiences at Boarding School in Belfast were Dickensian.

At the age of fifteen I developed the idea that I would like to become a composer. I was partly influenced by my friendship with a musically gifted boy called Derek Bell, who later went on to become the resident keyboard player and harpist for the folk group, The Chieftains – but he was also a serious composer in his own right.

Alas, he died recently while on tour. At school nobody took my artistic aspirations seriously, and it was “decided” that I should study languages, French and Spanish, at senior level and aim at getting to Cambridge University. I didn’t make that decision. It was made for me. I obediently did the study, took the exams, and scored a scholarship – means tested, so my father had to pay the University fees anyway. That infuriated me. I had earned the money. I didn’t want to be dependent on my father. It was too much like a debt.

As part of my studies I had to read the works of the 18th century French philosophers, Voltaire, Diderot, Rousseau and La Rochefoucauld. Their writings are among the most radical works ever written, much more radical, in my view, than any written later by Marx or Lenin They were at the basis of the French Revolution and the American Constitution. Beethoven’s “Ode To Joy” from his Ninth Symphony is set to verse by the German poet Schiller, and it expresses, in code, radical political ideas of equality. Schiller originally wrote “Ode To Freedom”, but, for political reasons change the word “Freedom” to “Joy” to avoid problems of censorship. “Praise to Joy, the God Descended, Daughter of Elysium”. To the revolutionaries of that time, “Freedom” was a secular deity of female gender. Her image is with us today, in New York Harbour. The Statue of Liberty. Liberty’s statue was also erected by Chinese students in Tianamen Square, in 1989, before being toppled by a tank.

So I was supposed to read this inflammatory literature as a purely academic exercise? A serious miscalculation on the part of the authorities. Their attempt to control my life began to backfire. I was already furious because of their puritanical disapproval of my wish to be an artist. I embarked on a series of dissident acts. Religion, according to Voltaire, was mere superstition. I refused to go to church. Consternation! I was by now a Cambridge scholar. How were they to deal with me?

I was summoned to my housemaster’s study for, as he put it, a philosophical discussion.

My housemaster was a retired military gentleman, who retained the title of major in civilian life. He had a peculiar way of talking. He would never look you straight in the eye. After about an hour of philosophy he said: “Well, Derek, that was all very interesting, and we’re glad you’re finding your reading stimulating, but I’m afraid I’m going to have to beat you. You’re a senior, and you’re setting a bad example to the juniors. We can’t have you refusing to go to church.” And he proceeded to administer the punishment with great enthusiasm and energy. Of course I counted the blows, and I became surprised when he exceeded the legal limit. 13,14,15, 16…at 17 I decided I had had enough, and I stood up, signifying the end of the ritual. He was breathing heavily and he was red in the face. It was a curious and very instructive outcome. The beating did not cure me of my revolutionary tendencies.

I was now marking time at school before going to university. The history master made a tactical error by recommending to me the works of George Bernard Shaw as general reading, Shaw gave me fuel for further retaliation. I gave a talk to the school Literary Society comparing the function of Jesus Christ decrying hypocrisy in Palestine, with the function of George Bernard Shaw performing the same service in Victorian society. The school found this very alarming. I learned that the English Master had three sleepless nights! It seems he feared it might be thought that I was comparing George Bernard Shaw to God – favourably! Blasphemy!! And at an officially organised school function! What if the Board of Governors got to hear about this? It was considered especially scandalous, I suspect, because I came from a religious background. This was Northern Ireland.

In the Major’s office again. No beating this time. Just: “Well, Derek we think you've been working too hard at your exams. We think you should go away and have a little rest.” I did. And I never went back. But I did go to Cambridge University. The school loved to have its scholars.

My first 18 months at Cambridge were a blur. Rebellion had exhausted me. My identity was non-existent. Obediently I worked through my studies. US Evangelist Billy Graham visited Cambridge. Out of curiosity I went to a “crusade”. I revisited family tradition and considered myself “saved”. It lasted for about two months, during which time I looked for converts. Who was the most unrepentant sinner I knew? Why, of course, my old school friend Henry “Joe” Lyde, now also at Cambridge. Along with Derek Bell, Joe had been my best friend at school. Joe had been a dayboy, while I was a boarder. He played jazz trumpet, collected records of the Dixieland jazz revival then current, and was able to go to all the movies which I, as a boarder, had to miss.

In the holidays we wrote extremely long and cheerfully ribald letters to each other, which my father discovered, and was furious. He had Joe’s letters returned to him, and mine to me. He destroyed my letters.

At Cambridge, Joe, who also wrote poetry, became an intimate of Ted Hughes, gathering with other poets at pubs. When I tried to “save” Joe by writing him an evangelical letter, he complained about it to Ted. And it was in a pub that Ted turned on me and very, very loudly berated me for my contemptible behaviour toward my former friend. I can’t remember exactly what he said to me, but I remember the content, and I’ve been able to reconstruct it to give some idea of what it’s like when Ted Hughes is angry with you:

“Oh, so you’re the idiot who tried to convert Lyde? I saw your letter and I’ve never read anything so pathetic in my life! Lyde told me he was a friend of yours at school. How could you treat a friend like that? If you know him at all, you must know that Joe Lyde is quite happy living his life in the way that he does, as a happy miscreant. It will take more than some drivel from you to persuade him to mend his ways. You should take a good look at your own existence before you start meddling in the lives of other people! Why don’t you stop trying to compensate for your own inadequacies by preaching at others?

There was more, in this vein. Of course I sat there pulverized and obliterated. There were several aspiring writers and poets there. Among them was one who later settled in Australia, Michael Boddy, who would achieve some renown by collaborating with Bob Ellis in 1975 to write ‘The Legend of King O’Malley”. He was vastly amused at Ted’s performance. He said to me: “Don’t worry about it, Derek. He’s a poet”.

As a result of that dressing down, I became able to re-invent myself, to become, once again, an individual capable of independent thought. It was Ted Hughes who kick-started that process for me. It was mainly because of Ted that I branched out. Did some acting. Played my guitar again. Went to parties. Chatted up girls. Met Sylvia Plath. I never got the chance to tell him, but thanks, Ted. You saved me!

I was then able to enter the world of the late 1950s and 60s unencumbered – the world of John Osborne, Angry Young Men, Marlon Brando, James Dean, Bill Haley, Elvis Presley and rock’n roll. By a curious irony, my language studies also gave me entrée to the work of an entire generation of French chansoniers who preceded the influx of singer-songwriters in the 60s: the Beatles, Bob Dylan and all. Before they emerged, I had already crawled back into music through Georges Brassens, Jacques Brel (who was Belgian) and a dozen others,

There is a Postscript to this story, thanks to more email chat from my old school friend, the one who told me I was in Sylvia’s Journal. Joe Lyde stayed in touch with Ted Hughes. He visited Ted and Sylvia in Devon. Sylvia would not let Joe into the house., because once, while dining with Ted, Sylvia and Sylvia’s mother, Joe had asked Ted loudly: “How’s the gigolo business going, Ted?” It sounds too much like Joe Lyde to be apocryphal.

Joe also became very close to Ted’s sister, who coincidentally, was also Joe’s publisher. If Joe had been the marrying kind, he might have become Ted Hughes’ brother-in-law. I can’t help wondering how Sylvia would have handled that.

They have all departed, leaving behind some poetry. The poetry explains much. But not everything.